A high-level understanding of a modern object detector’s architecture

Published:

What is Object Detection

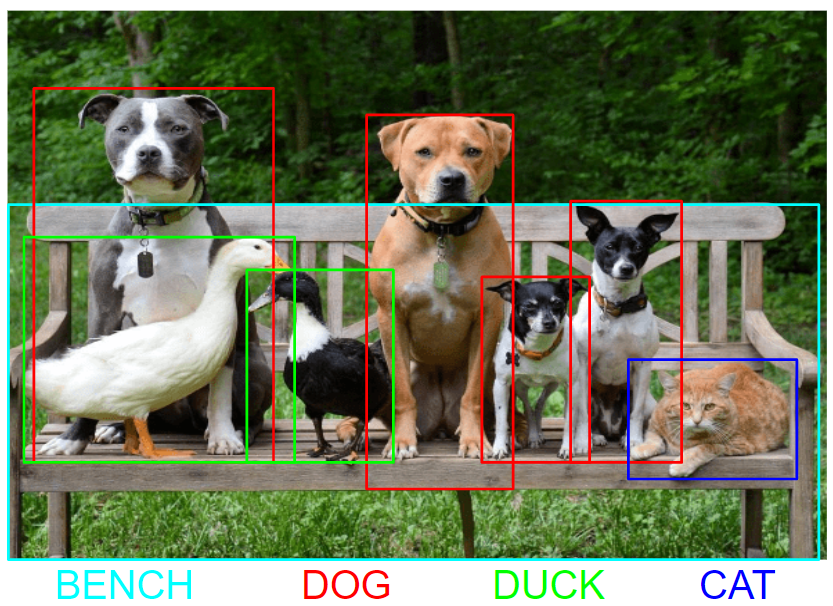

Object Detection is a vastly investigated task of Computer Vision - a scientific field that deals with how computers can extract high-level concepts from images or videos. In particular, Object Detection is all about locating elements of interest in an image and classifying them.

Architecture of a modern Object Detector

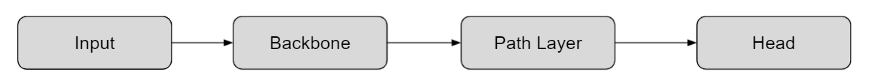

Nowadays, a detector cannot be considered a monolithic system, comprised by a single big component. It’s more appropriate to see it as an architecture composed by three main blocks placed in subsequent order, each one with its own specific functionalities but all linked together. These three elements, which will be the matter of this post, are named backbone, aggregation layer and head. When an image is fed into a detector, it will undergo three different macro-computations, one for each component: the backbone part will extract visual features that are meaningful for the task; the aggregation layer will, as its naming suggests, aggregate these features across different scales in order to enrich the information extracted; and, eventually, the head part will produce a bounding box for each object in the scene, together with a classification label.

Backbone

The task of the backbone is to extract visual information potentially important to identify an object. For example, if we want to detect a dog inside an image, the backbone has to extract those features that encode the presence of paws, tail, snout, etc.; moreover, the extracted features should also encode the position of themselves in the image as the head will further refine these information to output the localization of the dog. It is common practice to borrow the design of these backbones from the classification task, since they share the same goal at this stage of the architecture, i.e. extracting discriminative features that represent the class of objects. To make them compatible for the detection task, the last classification layer (typically a fully-connected layer) has to be removed, so that the following parts of the detector can access both localization and classification features before they are categorized in classes. In principle, any task that needs to reason on images, e.g. detection, semantic segmentation, super-resolution, can rely on features extracted by this network in order to go from a high dimensional pixel image to a smaller and more semantic representation. Typical operations used inside these models are convolutions, followed by pooling and normalization layers. Often pooling is replaced by strided convolutions as they achieve the same spatial subsampling while better at retaining information. A strong pattern in recent literature is to downsample the input image 5 times along the backbone, either through pooling or strided convolutions. This practice is largely related to the datasets used by the research community and their image input size. While the number of downsampling is nearly a standard, their position inside the architecture is a crucial part of the network design and greatly changes from one to another. When fed with an image at a given resolution, a detector’s backbone extracts visual features from it and gradually lowers its spatial dimensions. The output of the backbone is the concatenation of all feature maps right before being downsampled plus the final one, so that features from all different resolutions are provided to the next step in the detection pipeline. In particular, the output of a backbone with L downsampling layers (e.g. L = 5) will consist of a list of tensors of the following sizes:

\[ \left( \frac{H_i}{2^l}, \frac{W_i}{2^l} \right)\]

where (\(H_i\) , \(W_i\)) is the dimension of the input image. Having L feature maps with decreasing resolution, the output of a backbone is generally named Feature Pyramid, as they can be stacked vertically to form a pyramid as can be appreciated in Fig. 2.

Aggregation Layer

The feature pyramid produced by the backbone contains all the information needed by the head for localization and classification, but such information is located at different positions inside the pyramid: lower levels (higher resolution) have their features well-positioned, with finer localization potential; while features from higher levels (lower resolution) are highly semantic but too coarse for a proper localization. The aggregation layer aims to mix up feature maps from different levels in order to produce a final pyramid that encodes both aspects in all levels. Since the computation performed by the backbone goes only in one direction, i.e. from higher to lower resolution, the last level can benefit from the information of all the previous ones — but not vice versa. The aggregation layer typically adds the reversed mechanism in the network by letting information flow from lower to higher resolution levels. It is common practice to aggregate features only from adjacent levels of the pyramid, either by concatenation or summation. This architectural change has been shown to bring notable increase of performance to a great number of detectors. The introduction of aggregation layers is the main reason why backbone network now have a pyramidal output instead of just computing the last feature map. As a matter of fact, older object detector used to process only the last feature map received from the backbone and obtained some level of scale invariance by repeating the detection at multiple resolutions of the input image. Today, aggregation layers are considered the best way and the standard choice to approach multi-scale detection as it is more computationally efficient than running the detector multiple times. Of course, multi-scale detection is not mandatory and one can still design a detector to run only on the last feature map without any aggregation layer.

Head

The last component of a detector — and also the one which typically gives the name to the whole method — is the head and it is expected to define the final result of the network: placing a bounding box around each object and a label to denote its class. If multiple feature maps come from either the backbone or the aggregation layer, then a head is typically applied to each one of them separately. There is no restriction in the way a head can combine information from multiple levels, but working on one of them at a time makes the design more modular, e.g. a level can be added or removed without having to change the design of the head. As a result, this is the common practice in literature. A head needs to define three main aspects to work properly:

- how to represent the location (or absence) of one or more objects in the image - this is accomplished by the encoding step;

- how to process the input coming from the aggregation layer - this is defined by the model;

- how to treat errors made by the network in the learning process - i.e. the loss function. These three design choices will be explained in the remainder of this section.

Encoding / Decoding

The prediction of non-ordered sets of bounding boxes is not a trivial operation for a neural network and neither is trivial how to represent them: these information must be encoded in the network by its designers in a way that is suitable for learning. This choice is employed at training time to convert ground truth boxes to the network representation, but is also used at test time to convert from network predictions to output bounding boxes. The former case is referred to as encoding step, while the latter as decoding step. The most basic description of a bounding box is a tuple of six elements: four elements are used to inform on the location of the object relative to the input image, one element is used to describe its class and the last one convey the fidelity of the prediction, also known as confidence score. In case of a ground truth box, the confidence score is set to maximum value by definition. The following is an example of a bounding box descriptor:

\[ (x_1, y_1, w, h, c, s) \]

where \(c \in \{dog, cat, tiger, . . . \}\) is the class label and \(s \in [0, 1]\) the confidence score. In this example, the position of the bounding box is made explicit through its top-left corner and size information, but idempotent descriptions include center coordinates and size \((c_x, c_y, w, h)\) or top-left and bottom-right coordinates \((x_1, y_1, x_2, y_2)\). Detectors can be divided into two main families based on the encoding/decoding step, according to whether they use anchors or not. Anchors are some initial guesses of the possible detections present in the dataset. In an anchor-based detector, the head must evaluate each anchor and either produce a deformation of it that aligns with an object in the image or assign it a low confidence score to discard it. Through anchors, the developer can inject some prior knowledge about the dataset, like scale or aspect ratio, and greatly simplify the task and learning process. Anchors, on the other hand, may be difficult to tune and limit the generalization performance of the detector at test time. Moreover, anchor-based detectors must cope with the inherent ambiguity of having a large number of predictions, so it is not uncommon to have multiple anchors vote for the very same object — an ambiguity solved by a Non-Maximum Suppression step at test time that can lead to sub-optimal results. This is why many latest proposal in the field are focused on anchor-free approaches.

Model

The model consists of a sequence of layers that project the output of the aggregation layer into the same representation space of the encoded ground truth boxes. In this representation space, network predictions and truth data are comparable and the loss can penalize differences between them. While, the encoding step must be explicitly defined by the developer, the model will learn the proper projection function on its own as long as the tensor dimensionality is compliant with the representation space. As for the encoding/decoding step, detectors can also be divided in two big families based on their approach to model. Specifically, the two families are two-stage vs one-stage: as the name suggests, the former ones carry out the classification task only after having localized all objects; conversely, the latter architectures produce both results in one parallel step.

Loss

The loss function defines the amount of errors made by the network on the prediction of localization and classification of one or more objects in the image. Loss must account for errors regarding box coordinates, false positives and class labels. These errors are usually computed by three different functions that are then aggregated together with different contribution weights to form the final loss value. Different formulations or parameterization of losses can give completely different results.

This article is an extract of my master thesis, developed during an internship in Deep Vision Consulting, be sure to check them out! Moreover, this article is also published on medium!